Berliner Clemens Wilhelm makes exceptionally beautiful and very moving work, always thoughtful and more often than not leavened with a keen sense of the absurd. Sometimes all these qualities co-exist, variously jostling for our consideration.

For example, Die Linie (2019), Wilhelm’s journeying on foot, walking the length of the imposed post World War II boundary between East and West Germany, fourteen hundred kilometres from the Czech border to the Baltic Sea. Stopping every fifteen minutes to take a black and white photograph: the west on the left, the east on the right, and in the middle of the frame the variously overgrown patrol road. This remnant, this ghost of a divided nation, once known as the death strip is now a nature reserve and according to the artist a testament to the banality of power, “It’s an example of mind-blowingly stupid architecture.”

Die Linie comprises 975 pictures presented in 67 minutes with a musical composition born of original recordings made along the way. Wilhelm’s portraits of the landscape are breath-taking. But as we traverse lowland pasture, wheatfields, woodland pathways… there’s a niggling sensation that this route, this non-place, haunts the German psyche. “Even after more than 30 years reunification is an unfinished process, it’s painful to think about, some of the politicians, the architects of reunification are still in power, and they can’t admit to how damaging aspects of the project were. It is time that the process of reunification is re-evaluated. And much like Brexit, it’s a subject that’s hard to talk about. Emotions can become very heated.”

From the socio-politically infused visual studies to works that address the evolution of the earliest art objects, ecological issues and mass tourism. “I have made work about climate change for many years, long before it became a ‘hot’ topic in the arts,” Wilhelm explained. His video titled A Horse With Wheels (2017) poses the question, ‘Can we get closer to our ancestors who made the first art objects? Does it help our understanding to witness the same sights and environments? Have we changed at all since the Ice Age, or is progress a deception? What do we really know about our past and why do we want to believe that our ancestors were primitive? Is the camera so different from a carving knife?’

Such profound questions are adroitly addressed in A Horse With Wheels. Made over the course of seven years, the film takes us from prehistoric caves in France, following a herd of 1000 reindeer in Norway, to the vast expanses of the Scottish Highlands and an anthropological museum in Germany. An intriguing question is posed, ‘How did such an unforgiving, albeit awesome, landscape give rise to and affect the very earliest efforts by mankind to produce art, that practice which researchers call the ‘useless tool’, art as a tool for not just representation but thought and reflection?’ A 13,000-year-old mammoth tusk carving of a swimming reindeer is a mind-boggling artefact. Seeing Wilhelm’s Nordic sequences shot in the Arctic, featuring steep hill terrain inhabited by reindeer – where no sky is visible, just the elegant beasts traversing scrub and rock – and suddenly ice age cave art on rocky walls look more like literal rather than abstracted representations.

From the genuine wilds to a cynically constructed reality: The End of Something (2022) records time spent in a park adjacent to the Eiffel Tower in Paris. During the last summer before the Coronavirus turned ‘normal’ life upside down Wilhelm’s depiction of the daydream of mass tourism – the blessing and curse of France’s capital city – shines a light on late capitalism’s contrived distractions. “It’s like the tower of Babel, people from all over the world gathering to enact a prescribed leisure, recording sundry moments on their smartphones and thereby feeding the algorithm around this monument to tourism. It’s strange, almost like a religious festival.” In amongst the seemingly mundane pleasures there are moments of poignant disquiet. A woman is seated on the grass drinking from a wine bottle and feeding bread to birds when a figure whose face we can’t see steps into the frame and motions towards the bread, then puts her fingers towards her mouth. At first the seated woman waves away the stranger’s request but then – maybe realising the irony of feeding park fauna for fun but refusing to share with a fellow human – she breaks off a chunk of baguette and hands it over. It’s a moving scene amongst very many vignettes that are attendant on this touristic ritual. Asked how he captured so many intimate moments in public space Wilhelm explained, “While I didn’t ask permission to film, I was out in the open with a pretty big camera! People are so used to being under surveillance they barely see cameras. So yes, it’s a way of working that does capture affecting moments, gifts that arise if you just sit and observe for a long time. Real life happens when you wait.”

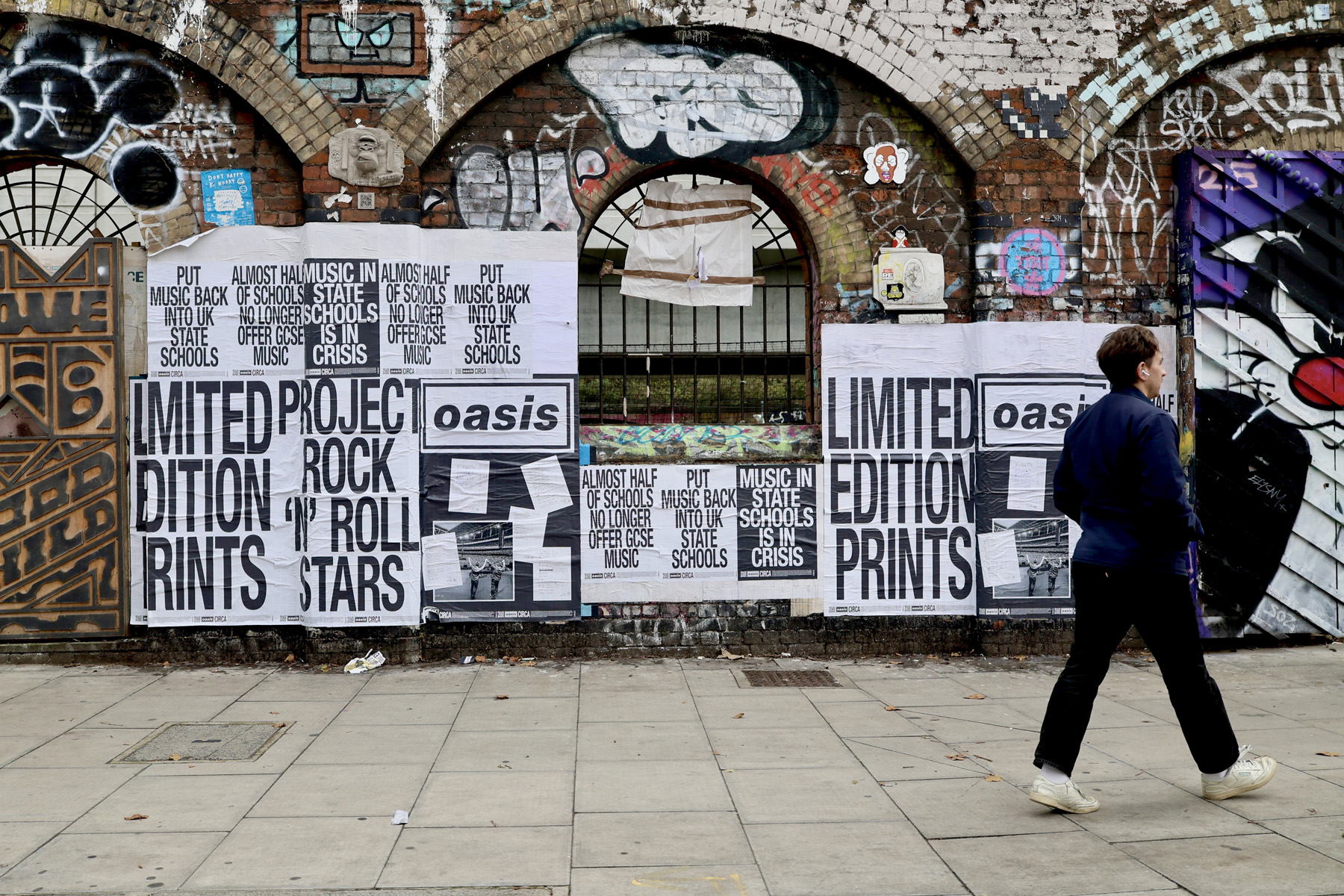

For his collaboration with UNCLE Wilhelm revisits an ongoing project that began in 2008. ‘MACHT NICHTS’ is an ambiguous German phrase. It can be understood as a pacification: “It’s not so bad, it doesn’t matter.” Or it can be read as an order: “Do nothing!”, “Stay passive.” And then, when it appears as a message trailed behind a plane or illumines the city via a huge digital display on a decommissioned gasometer or takes up residence in a trendy Berlin bar or features on a pair of badges – one of which we see handed to the ex-German chancellor Angela Merkel – ‘MACHT NICHTS’ evolves into a discombobulating utterance, an uncanny invitation/instruction that without knowing who the ‘sender’ is becomes a sort of doublespeak. Akin perhaps to language deployed by wily politicians et al who disguise their agendas with mealy mouthed words.

There are two versions of the poster appearing on the streets of Berlin: white text on a black background and vice versa. Displayed alternately and in a chequered formation the stark design and intriguing message seeds the urban environment with ambiguity, a subtly disarming intervention that echoes extreme ends of ‘Don’t worry/Do worry’ tactics used to pacify/scare peoples variously excised by issues such as immigration, the sharply rising cost of living, eco-crises, social cohesion, the effects of AI on employment, etc., etc. UNCLE are excited to support an artist/filmmaker whose work is visually seductive, mesmeric and then goes much further to explore key socio-political, psychological and philosophical concerns.