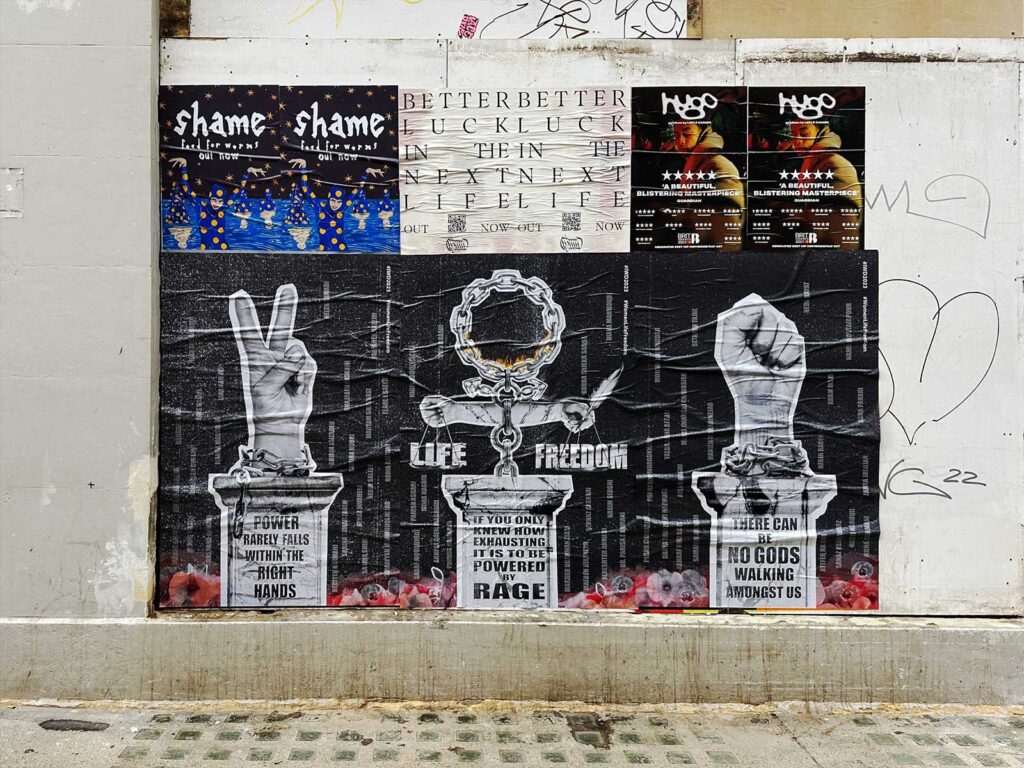

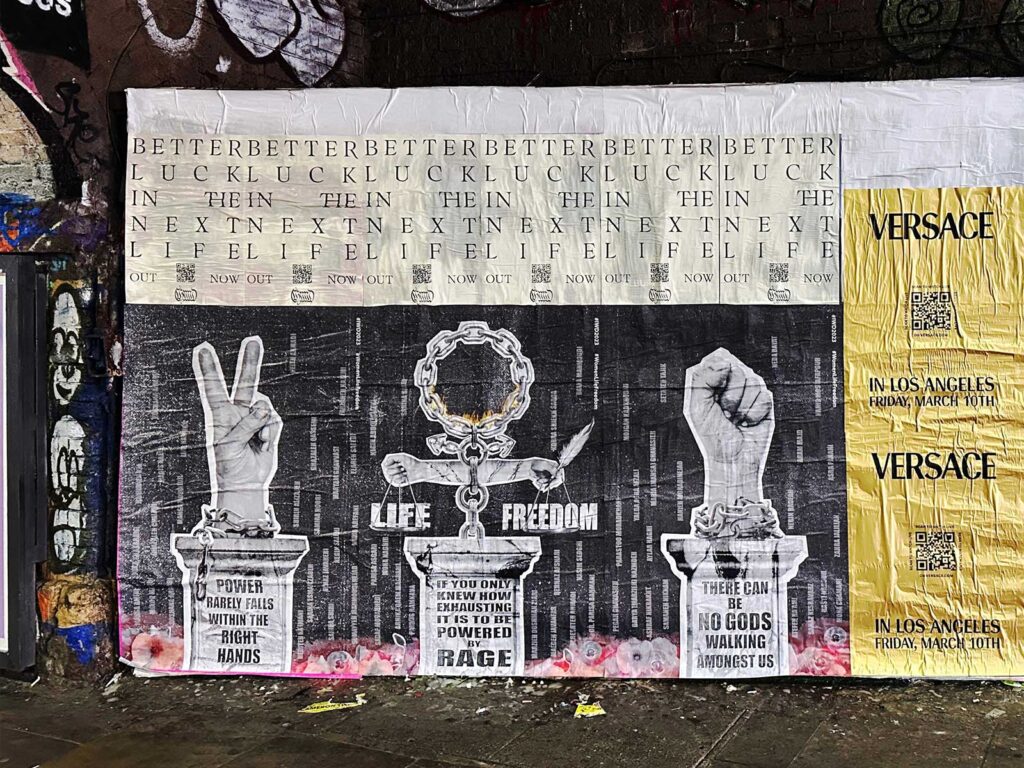

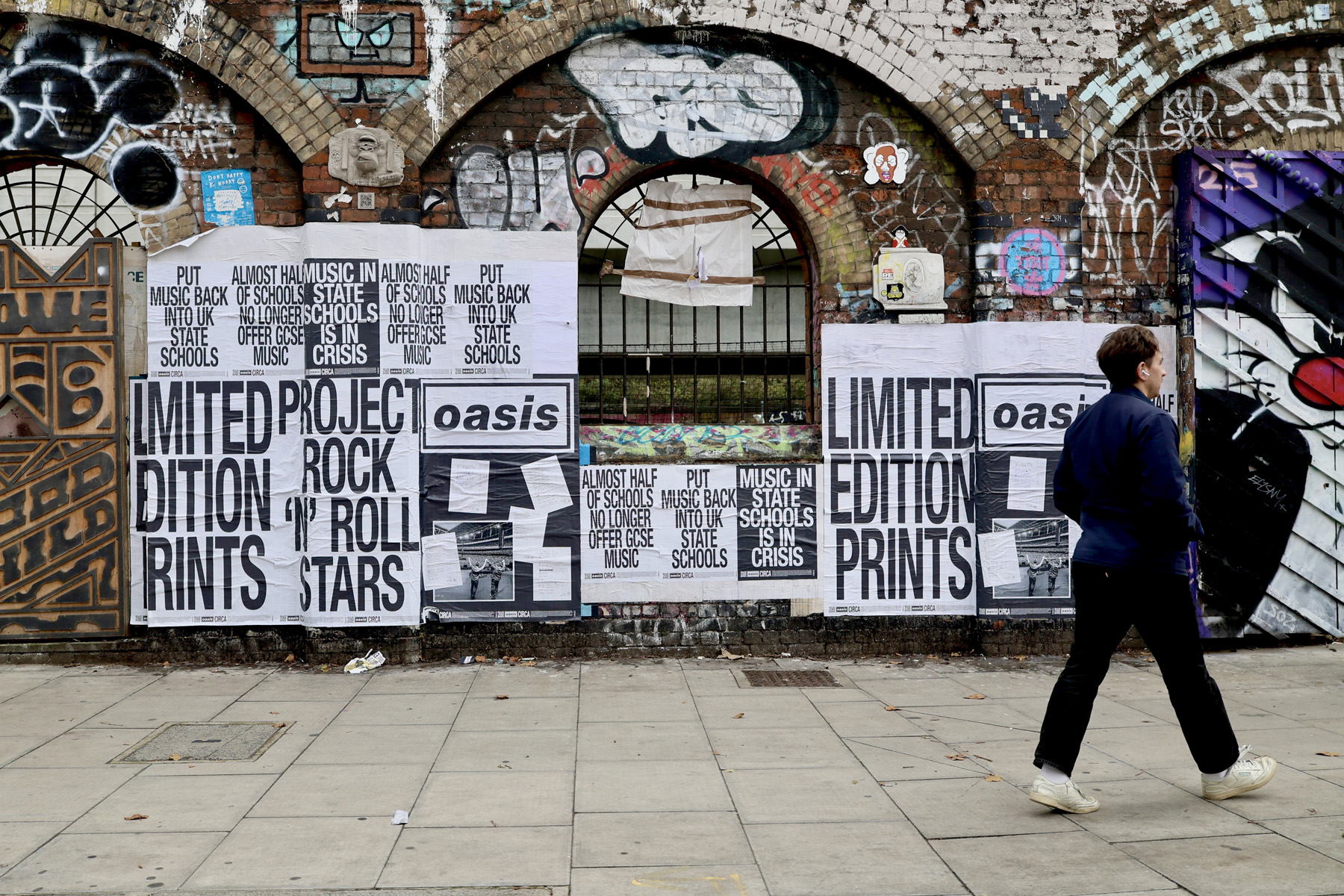

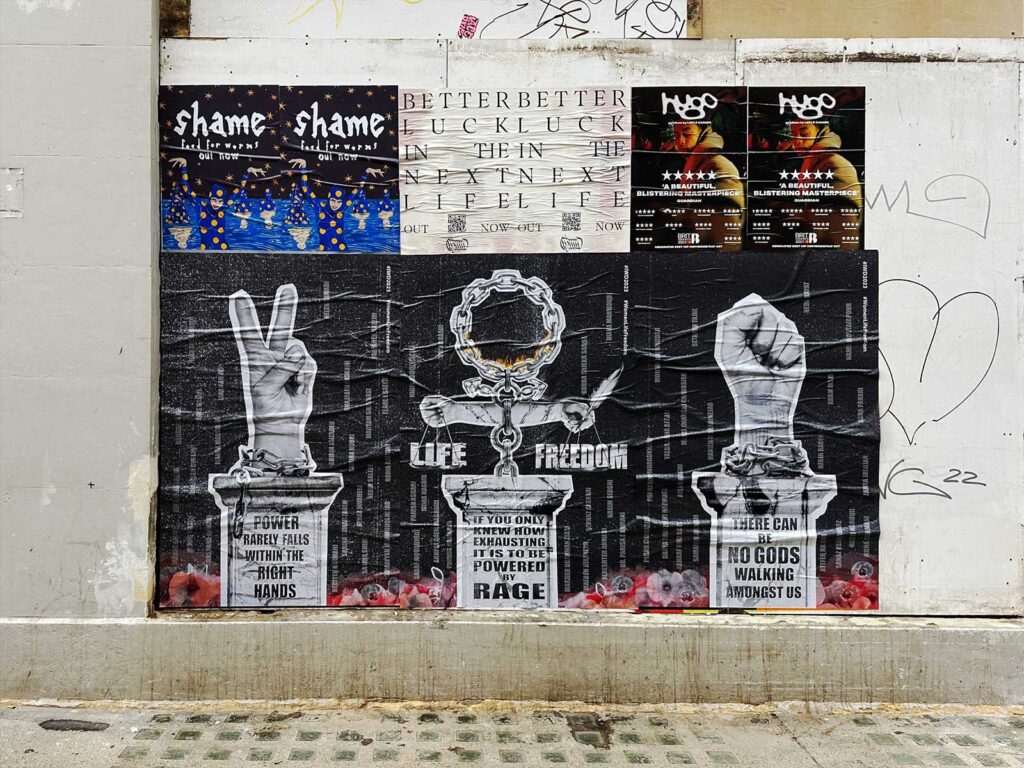

Acclaimed artist Aida Wilde is no stranger to speaking her mind, her name being synonymous with bold and pointed slogans that sum up the world she sees around her. For International Women’s Day UNCLE collaborated with Aida to get the powerful piece she designed in front of eyes across the UK.

Wilde is a multifaceted creator most prominently known for her screen-printing, but she also creates in many different mediums including printmaking, street art, installation and murals. Her pieces are responsive to issues surrounding politics, gender, education, gentrification and equality and have been displayed internationally at venues like the Victoria & Albert Museum, Women’s Art Library, Goldsmiths, Vienna’s Fine Art Academy, Somerset House, the Fitzwilliam Museum, and Saatchi Gallery to name a few.

The artwork for this collaboration was designed to somewhat be a homage to Wilde’s Iranian heritage, being born there and later fleeing to the UK during the war. This experience is unfortunately not a unique one, with so many women being affected in similar ways, and many still facing extreme oppression in the country itself. The slogan featured on the piece promotes both reflection and action – “Power rarely falls within the right hands”; “If you only knew how exhausting it is to be powered by rage”; “There can be no Gods walking among us.”.

Aida has been active since 1993 and is disruptive in a world that didn’t always treat her fairly. Her womanhood never defined her, but it certainly informed her experience and as she looks back, she can see the true impact it had on her journey. We discussed this and her artistic beginnings, experience in the field and the importance of the work she does.

WHAT ARE YOUR MAIN INSPIRATIONS AS AN ARTIST?

When I was at university, I stopped reading magazines and most newspapers. You’re taught to follow trends and fashion and keep up to date, so I consciously decided not to do that. I’ve shut myself off from media, the only thing I really look at now to inspire me sometimes is what’s trending on Twitter. I make a conscious decision not to follow anyone trendy or upcoming, any painters and printmakers, I just don’t want that to cloud whatever vision I get. I want everything to be very organic. Even if I have seen something and it does influence me, I’ll know that I wasn’t looking at that certain artist or that certain thing. Most of my inspiration comes from the past, be it archives and looking at political posters, fine art prints and what occurred before us. There’s nothing new – I believe you can’t do anything original, so I think for me to look in the past and bring a sort of a fresh perspective onto things, that’s what inspires me.

WHERE DO YOUR ICONIC SLOGANS COME FROM?

I’m a bit dyslexic so the majority of my better-known slogans have always come from me reading something wrong, like whether I stumble across a newspaper headline passing by and I’ve read it wrong, replaced one word with the other one and think it makes so much sense. A lot of the slogans come to me like a whisper or a dream, it’s really strange, then you get this compulsion that you can’t stop and then you need to just create that piece of work. I write a lot of notes, sometimes one word just comes into my head and it’s perfect, these notes trickle down to what becomes either pieces in my graphic design or work on the street.

WHAT IS IMPORTANT TO YOU ABOUT YOUR ART?

I’m not here to please everybody but I think what I do is for everybody. I like to think that it is for a collective consciousness. I don’t over complicate the visual language so anyone can just stand in front of it and understand. That’s the main thing, if people understand it straight away it means maybe we could all relate to each other and it could be talked about, shared and understood. I don’t like overcomplicating things; accessibility is so important when it comes to art especially in the age where people want to overcomplicate. Yes sometimes, it’s fun to dig deeper meanings but you know so many messages are overdesigned.

HOW DID YOU COME TO SCREEN PRINTING AND WHY IS THAT SOMETHING THAT YOU WERE DRAWN TO?

At school I was doing art, but I wasn’t very good, I just had a really strong desire to do it. I was good at other stuff like business studies, and I think that’s really helped me with my career understanding economics and things like that. Some of the other kids used to be able to screen print by stencilling and I was just so envious. Then when I turned 17, I was trying to do it by myself, and it just wasn’t working. I then started to do my foundation course in art and design, and they had a screen-printing facility and me and my best mate who I still collaborate with went into this screen print room. My work was photography based, I still loved photographing things and blowing them up and collaging them. I transferred all my photographs onto the screen and literally my work changed within a week. At my first crit showing the prints I always remember the teacher who said, “Oh my God, I think you found what you’re meant to do” and I think I was always meant to do it.

WHAT WOULD YOU SAY IS YOUR FAVOURITE PART OF YOUR CREATIVE PROCESS IS?

I can tell you what my least favourite is cleaning screens, it’s so boring and I’ve got to clean this screen today and expose something, you know it’s those labour things. But I always wanted to be self-contained, to be involved from the beginning, the idea conception, making the artwork, printing/painting with the screens – so I’m all in one. So much labour goes into screen printing, the hours of just stripping screens, coating screens, cleaning exposing, touching up you know and that’s just for one piece.

I love that sometimes you could look something up digitally, choose your colours you want, but it can all change once you start physically laying down those layers and how they interact with each other. I love that process; I like how one layer sometimes dictates your next layer. It is all so satisfying in the end.

HOW HAS BEING A WOMEN IN THE CREATIVE SPACE CHANGED FOR YOU OVER THE YEARS?

I started with slogan T-shirts, and they always used to be a bit angsty, that’s how they started out, it just felt like a natural thing. When the credit crunch hit, and I had to close my shop, I started doing more political stuff. At that point I met a lot of street artists as they were up and coming and I was printing for them as well as my own. It was like the beginning of something, and a couple of the guys said I had something to say and that I should put some work up in the streets. Later around 2008, an East End gallery approached me who’d seen some of my artwork on T-shirts and said have you ever thought about doing these on paper- as editions and Its many years later that I realised I’d been using my talent and my gift to serve the men I was working with – and this went on for many years. I was printing for everybody and as I began to rise slowly, I started noticing the minute that I was doing well for myself – I was doing more installations and more international shows, this balance was shifting in the way they perceived me. I didn’t realise for how many years I was desexualising myself to keep my integrity and reputation intact. I just became this little tomboy in a hoodie, I kind of lost myself and I think it was this realisation of yes you empowered me to do this but at the same time I’ve completely lost track of who I am and how I am seen as a woman. I pulled back, stopped most of my printing for men and set those boundaries, and after years of collaborations, they all dispersed. I think that’s when the penny dropped.

HOW HAS BEING A WOMEN AFFECTED YOUR ART?

Women especially overcompensate I think, we know that sometimes we have to work twice or three times harder than men. So, I used to over produce just to compensate and demonstrate my productivity. I suppose I lost my trade but there was a point where I questioned – is the process fulfilling enough for me? The making process is a form of therapy, it’s a form of escapism and it’s a form of me trying to prove myself to something. I don’t even think I’m proving anything to myself anymore, I think I’ve done that. Not deviating from my vision, keeping my integrity and having a big voice and not compromising has given me the freedom to what I am able to do today – but this obviously comes with heavy price.

FEMALE ARTISTS YOU LIKE AT THE MOMENT?

Sarah Lucas has just created a show Big Women in Colchester, where she’s focusing on heavyweight, mid-career female artists. I love that she has brought attention to talented women of a certain era/age with this curation, as we all know, the shift in attention and current artistic opportunities are very youth and style orientated or on the other side, the forgotten/undiscovered, dead/dying female artist. What happens in middle… nobody knows?

HOW HAS YOUR HERITAGE AFFECTED YOU?

I’ve obviously come from a political background; my father was a sort of government figure, and we got political asylum because my dad was murdered by the government not long after the 1979 Iran Revolution. I’d love to go back to Iran; I’d like to see my dad’s grave. But I’m so proud of Iran, when you think about the state of the Middle East and Middle Eastern men and how most of them are portrayed as being misogynistic. The Iranian men have really shocked me standing there with the women shoulder to shoulder willing to risk everything in the recent uprising/revolution. We also need to focus on these men that are standing fighting alongside the women and being killed. I’m just sad I’m not a bigger part of it.

TALK US THROUGH THE DESIGN OF THE WOMEN’S DAY POSTER?

I deliberately wanted to make it feel like a throwback to a 60s or 70s political graphics, and knew I wanted to do a collage as this is how most of my work starts, so I cut things up at the beginning of the screen-printing process. The hands are mine, my mum’s and my two sisters one of them being (Ziba Karbassi) she is a really great eminent Iranian poet so she’s the one holding the little quill in her hand to symbolise the liberation that a pen/writing can do for us (especially when you think about the banning and the weaponization of an educational rights to girls and women of Afghanistan by the Taliban currently). The rage slogan was an angry day, and it came to me in an instant, like a flash and I literally stopped what I was doing and scribbled it down on a piece of paper. Then that night I storied it and right away it blew up. So many people wrote to me saying you’ve nailed this. The background of the artwork consists of a list of names of all the women that have been killed in Iran from the current uprising since the murder of Mahsa Amini in September 2022 – December 2022. Accessing current and correct information is quite complex – the figures are much higher than what we could find but at least, this piece can take the anonymity out of some of these brutal killings. The names are falling and rising in a ghostly stream from the poppy fields at their base – honouring and humanising the countless women and girls lost to this ongoing state-sanctioned femicide.

Controversial as this slogan ‘There Can Be No Gods Walking Amongst Us’ can appear to be interpreted, it is a direct reference to Iran’s autocratic ruling – to imply that if we want to achieve equality as humans, NO ONE is above anyone. The same implication goes into the other words on the right plinth states: “Power rarely falls within the right hands.”

Sigh / 15 / Revolution

“From everyone/ more than everything/ From all/ More than everyone ever/ I believe in my own chest/ In the moment of the bullet.

Poem by Ziba Karbassi

Translated by Ziba Karbassi and Nazlee Radboy