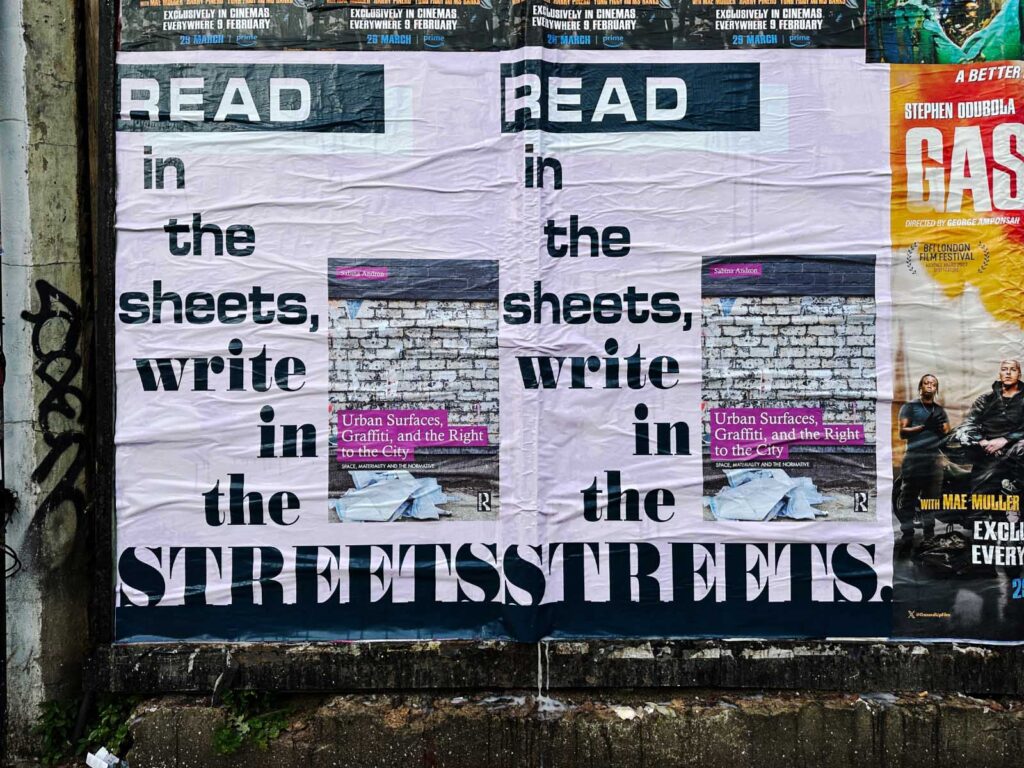

In just a couple of hundred meticulously argued and illuminatingly illustrated pages, Postdoctoral Fellow in Cities and Urbanism Sabina Andron has produced a book that examines, challenges, and radically reorientates the possibilities of engaging with our urban environments, and thus to experience cities in entirely new ways.

As set out in the introduction to Urban Surfaces, Graffiti, and the Right to the City, “Cities code an incredible amount of information in their publicly displayed signage and in the ways they present themselves through their surfaces. When we move through cities, read about them, or watch them on the screen, we constantly decode these signs and interact with urban surfaces. We employ them, and they guide us. We protect them, and they inform us. We beautify, vandalise, and clean them, and they remain indispensable to urban rhythms, affirming the presence of bodies in the city. City dwellers, government, commerce, art, weather, pollution, law – all these bodies need surfaces to communicate, and their messages are stored in the archive of the urban surface.”

Andron’s landmark text breaks down into four main areas. Semiotics is defined as the study of both the production and interpretation of signs and symbols and the first section of the book, titled Surface Semiotics: A Manual for Knowing Surfaces, introduces us to fresh ways of viewing all manner of urban inscriptions, and not just in spatial, visual and material terms. What the author also shares are interpretive tactics through which we can better read and understand the multitude of entangled images and texts that surround us. And what’s also revealed are underlying issues to do with agency, order, justice, and power, etc., that are variously denoted by so many forms of often overlapping inscriptions that populate our urban surfaces. And, of course, we’re not just talking about ‘writing on the walls’, but building elevations and facades, fences, billboards, street furniture and all the other publicly accessible and visible boundaries in our cities. By the end of section one you may find yourself conducting an interview with an urban surface, and it turns out this can be a conversation that ultimately says as much about the interlocutor as it does about the city.

Section two, Beyond Art and Crime: A Critical History of Graffiti and Street Art is an exhaustive investigation. Academic, literary, public, administrative and media attitudes are examined to arrive at much more nuanced consideration of this historical and contemporary phenomena. Andron argues that graffiti and street art’s valorisation and celebration – be that through coffee table publications, walking tours, absorption into the fine art gallery system, online forums, co-option by property developers and tourism – has turned what can be seen as democratic and inclusionary urban visual culture into one of “signature and authorship, stabilising the practice institutionally and making it easier to predict and monetise.” Time and again what’s so informative and refreshing about Andron’s approach is her willingness to counter hitherto accepted views – be that aesthetic, literary, sociological, political, etc. – about her subject. And she very effectively counters tired binary formulations re. graffiti and street art such as, “Is it crime or is it art?” It turns out neither of these pigeonholes take us anywhere useful. Andron teases out the much more productive categories of “communication, engagement, urban language, spatial practice, cultural production, multimodal expression, emplaced occupation, public discourse, networked semiosis, surface politics – all of these and more, just not art or crime.”

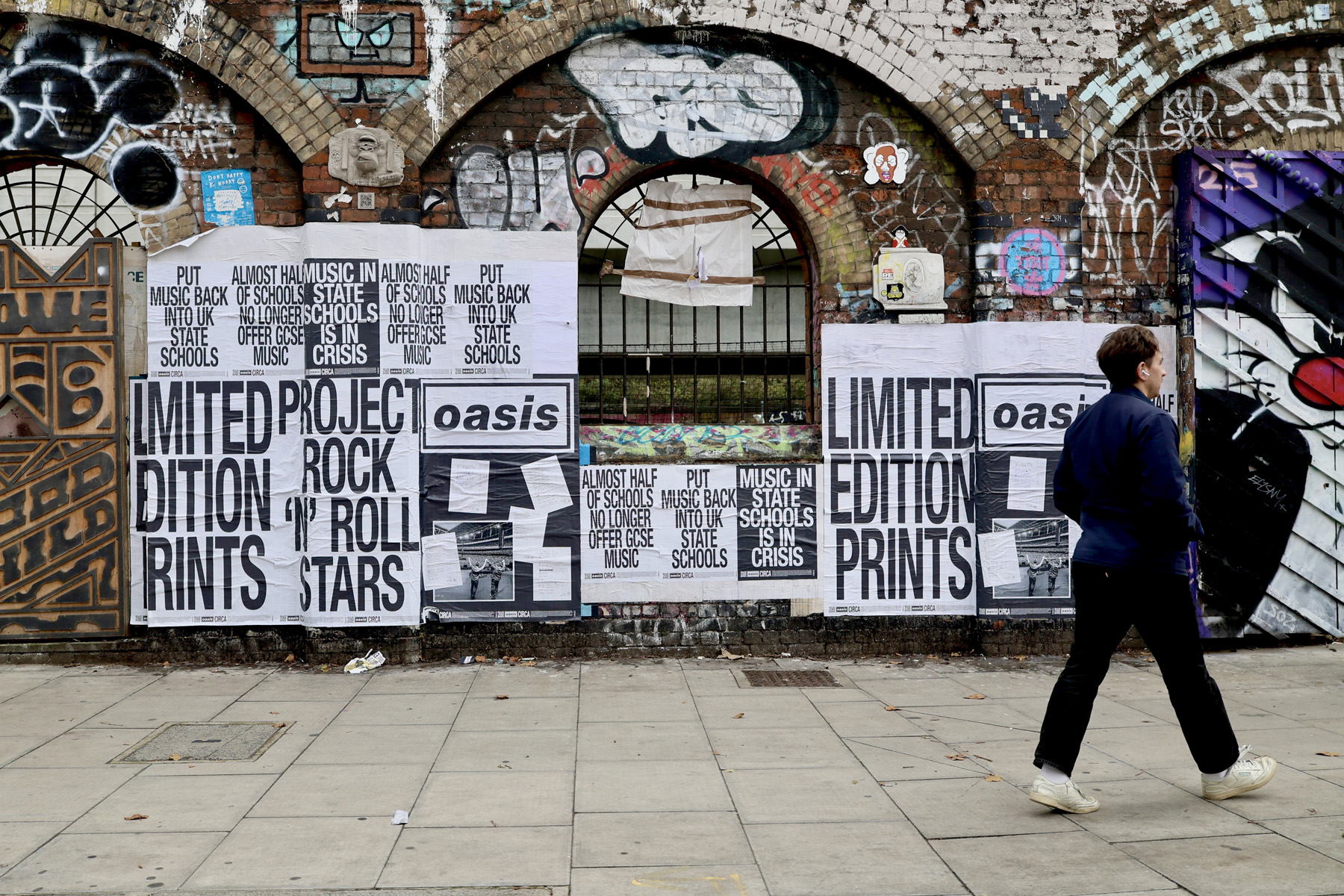

In section three of her book Law and Graffiti: Property, Crime and the Surface Commons Andron takes us on a deep dive into that “most turbulent of locations”, the surface lawscape. Andron calls out the ‘broken windows theory’ as lacking proper evidence to support links between (surface) disorder in neighbourhoods and links to serious crime. And while she argues that contested urban surfaces illustrate links between property, exclusion and public order, “they also represent political possibilities of establishing an urban commons and a claim to the right to the city.” Urban surfaces may be municipally or privately owned but “they expand through public use, generating new spaces in public sight like an open-source book of urban production and participation.” In the constantly evolving, multiple and simultaneous occupation by signs, tags, stickers, posters, pavement sale paraphernalia, etc., etc., in this fight for visibility, Andron discerns in the agglomeration what she refers to as a form of surface justice. It’s the very precarity, the ongoing jostling for conflicted space, that perhaps counter intuitively affords ongoing cultural and political value so that, in another neat reversal, surface activity that might be deemed antisocial, criminal and threatening instead becomes “socially and creatively engaged contributions to the surfacescape.”

Section four of the book Leake Street London: Legal Walls and Deep Surfaces is a distillation and further development of a project initially undertaken in 2013. The author identified ten different sections of wall in a legal graffiti tunnel running underneath the former Eurostar terminal at Waterloo station, visiting and photographing the changing scenes every day for a hundred consecutive days. It’s a tour de force of attention, visual and material, to painted layers inches thick in places. Andron goes on to say in her conclusion “From New York City trains in the 1970s to contemporary murals and graffiti layers in London’s Leake Street, the semiotics of surfaces not only reflects but also constitutes urban identities. Scribbles, placards, drawings, traces, white-washed walls, posters, signboards, and inscriptions are visual and material translations of the urban organism as complex, contradictory, plural, and chaotic as the city itself.”

UNCLE’s street poster campaign helping promote this scholarly, informative, surprising, and absorbing book is both a privilege and, in some ways, a symbiotic partnership. Like Andron, UNCLE sees urban surfaces as sites to ‘read’ and ‘write’ on, opportunities to contribute to the seemingly forever mobile conjunctions and to celebrate the rich publicness of our cities.