“Breakers means anyone breaking a mould – not just dancers, but people carving their own path.”

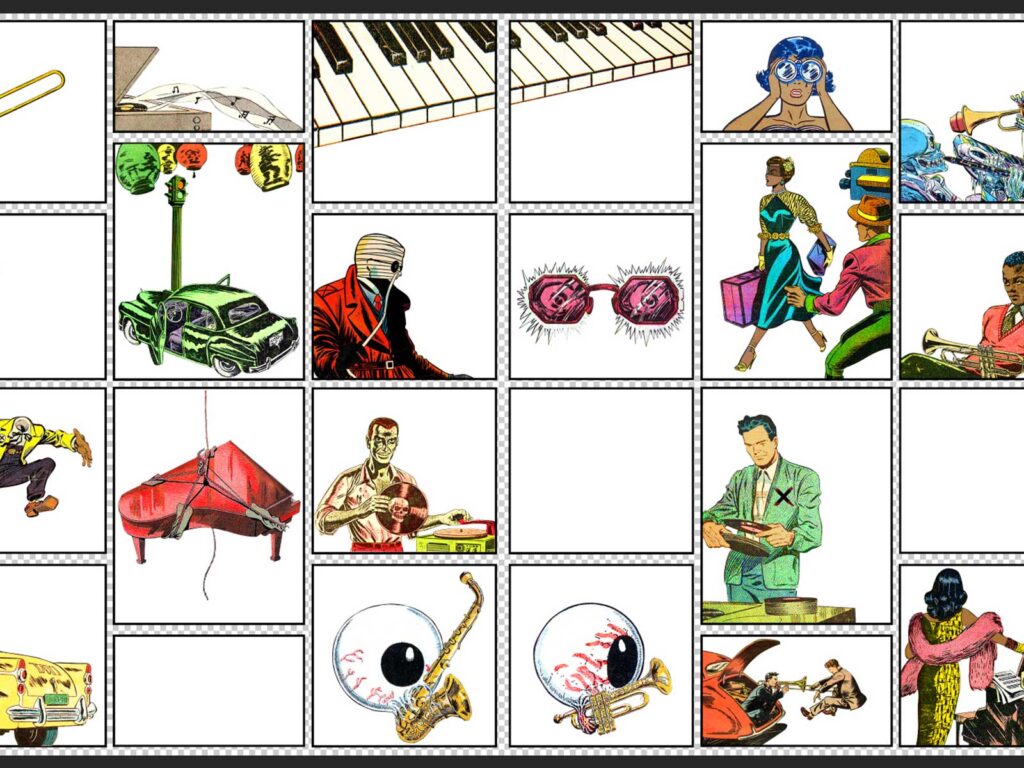

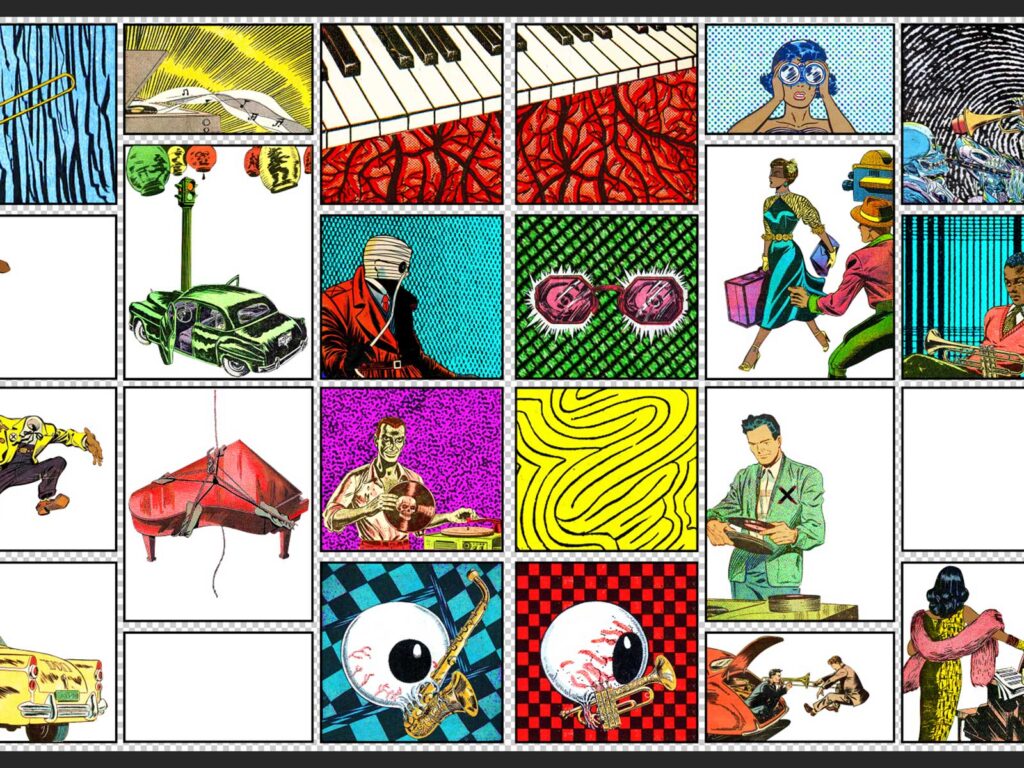

Now five issues deep, Breakers has evolved into a bilingual, community-built project run between Paris and Montpellier, with an extended network of contributors around the world. It’s as likely to include essays on dance as it is portfolios on graffiti, interviews with hip-hop academics, or short stories that orbit the culture in more abstract ways. Its design sensibility, led by Esguerra is raw, tactile, and always evolving. More than just a magazine, Breakers has become a kind of ecosystem: producing events, collaborating on video and editorial projects, and working with cultural spaces across France.

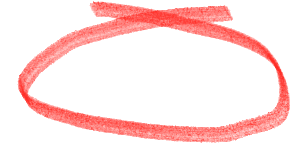

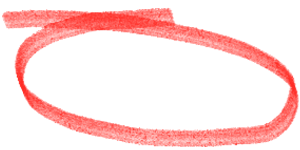

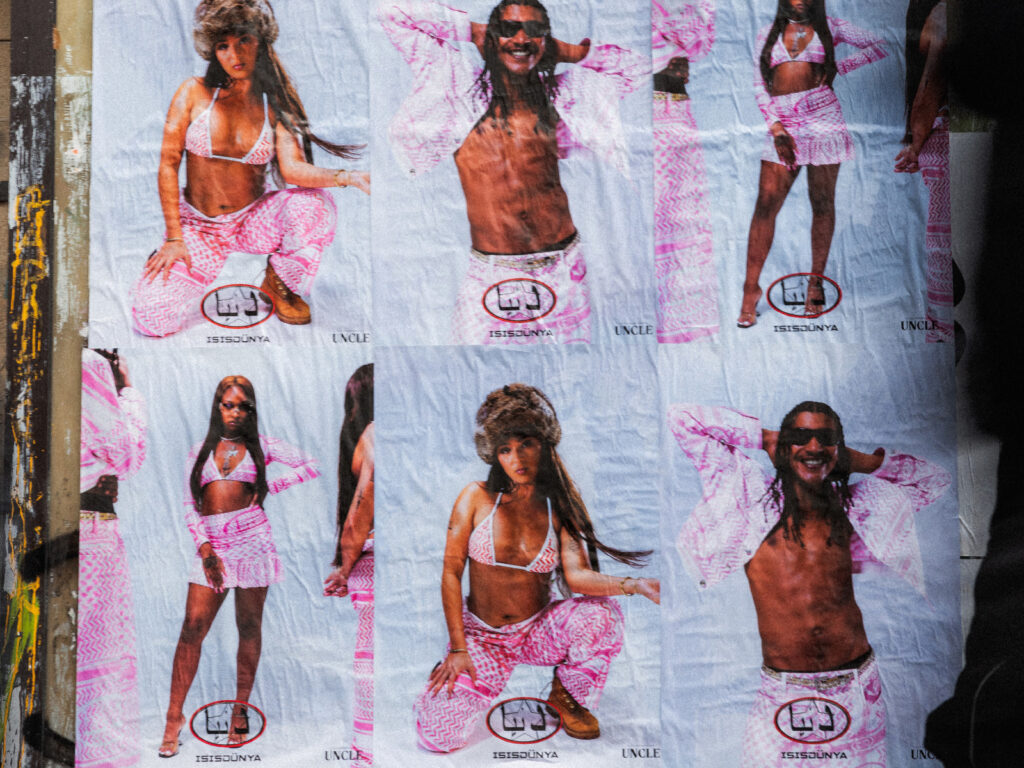

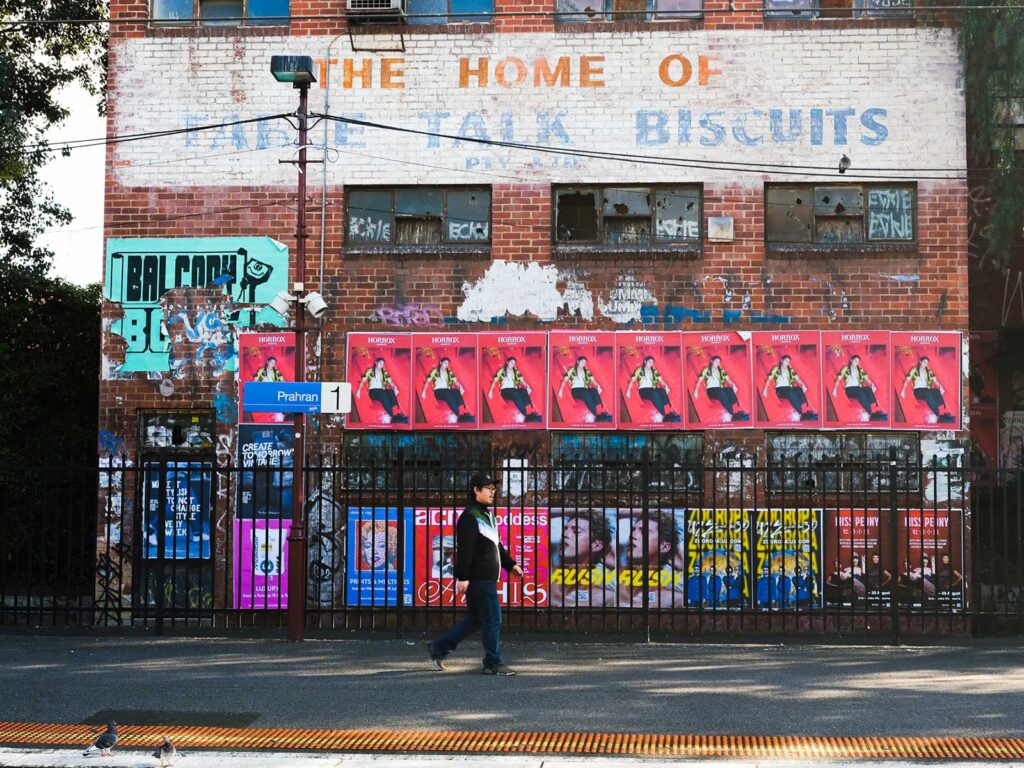

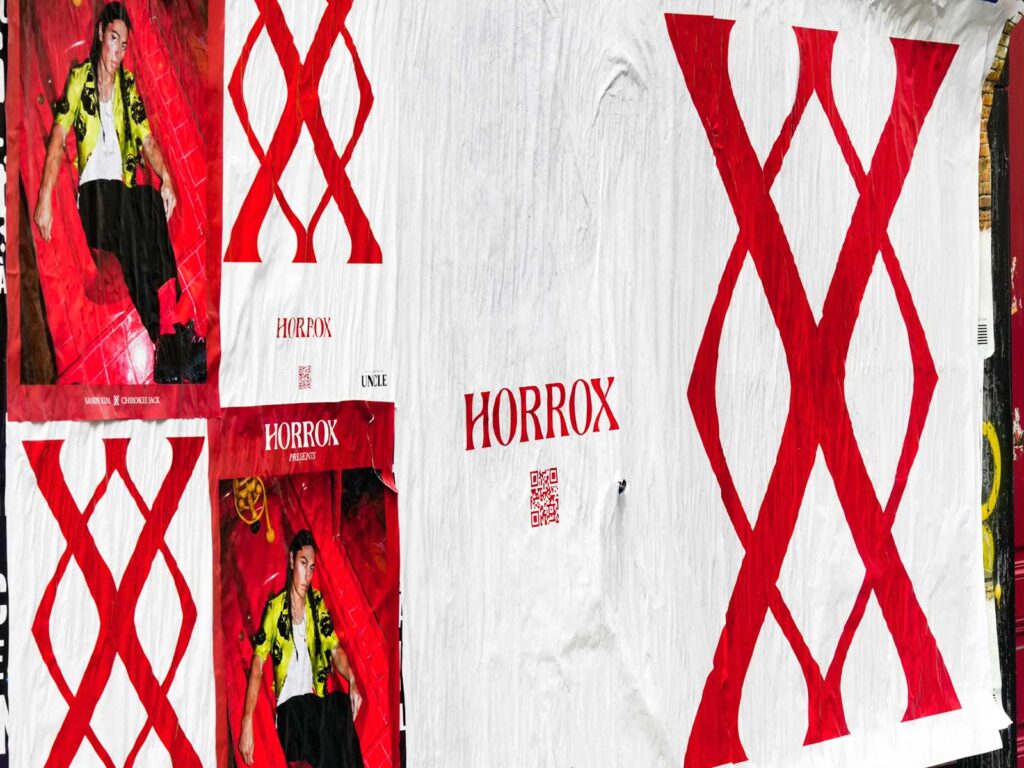

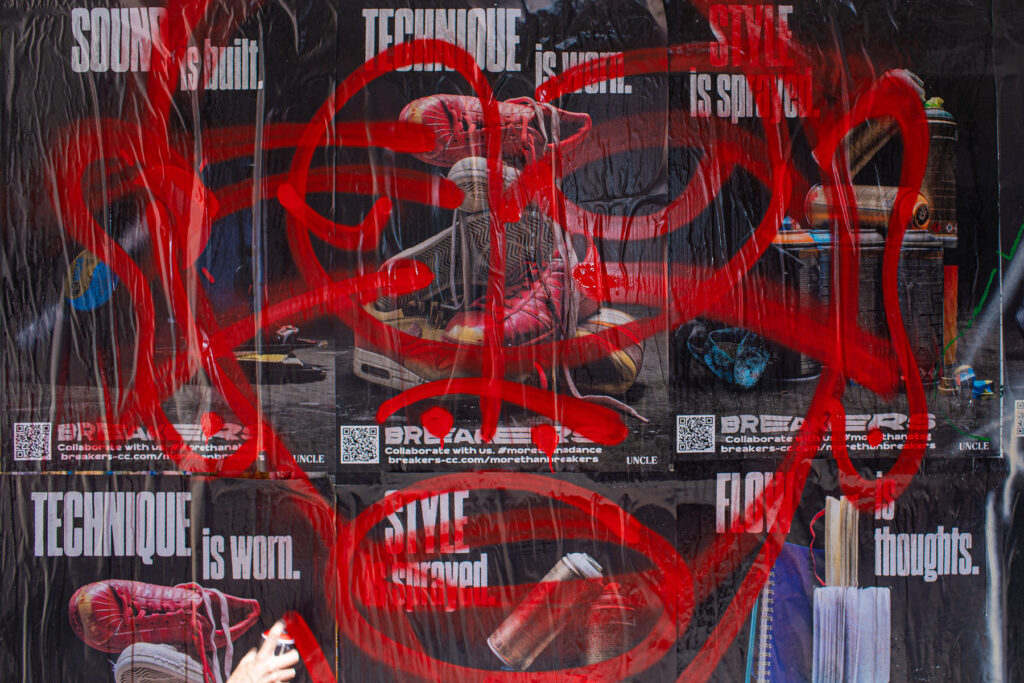

Their latest collaboration with UNCLE sees Breakers return to the street, this time through a wildposting campaign that turns pages into posters. Bold quotes pulled from past issues now line Paris walls, inviting passersby into the world they’ve built. “It’s not just marketing,” says Tom. “It’s part of our DNA. DIY, physical, public-facing. Just like breaking itself.”

At the centre of everything is a belief in community over clout. Their Tribe Tales event series, channels that same ethos: bringing crews together not just to battle, but to build. For Breakers, success isn’t measured in followers or sales, but in relationships and in staying true to the culture that raised them.

What follows is a conversation with the two co-leads Tom and Sebastián, about their creative process, how to grow something without diluting it, and what it means to build a platform that’s local, global, and rooted in real movement.

TOM: I’m Tom Chaix. I was born in Paris but didn’t grow up there, I’ve spent most of my life abroad. I started Breakers Magazine in 2021, during a period of reset on Réunion Island, just off the coast of Madagascar. I was trained as a civil engineer, but I’ve been breaking for over a decade now. That mix of technical background and creative curiosity led me to try something new. The magazine began as a personal experiment: a way to learn design, writing, and publishing on my own terms and to offer breaking the kind of visual and editorial culture that exists in skateboarding or surfing. I did the first edition solo, but thanks to that, I met Sebastián and from there, we started building a collective.

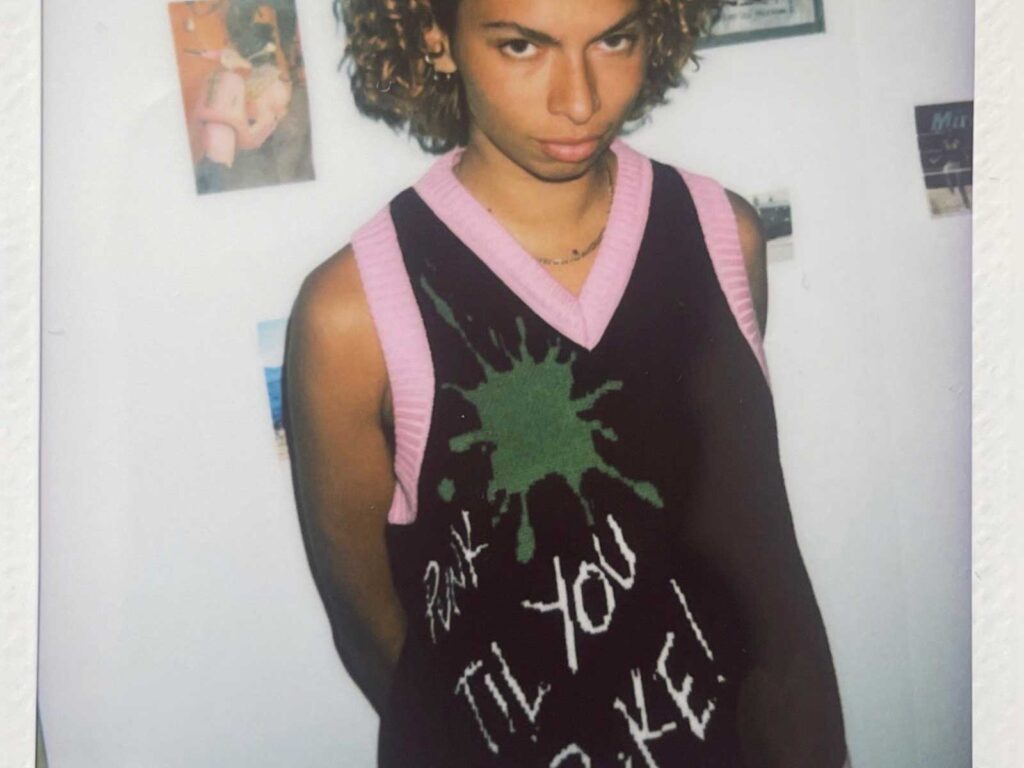

SEBASTIÁN: I’m Sebastián Esguerra. I grew up in Colombia and moved to France a few years ago. My background isn’t in dance, it’s in skateboarding, football, photography, and design. I’ve always been close to hip-hop through friends and creative projects, but it was when I saw Tom’s first issue of Breakers that I really felt connected. Even though it focused on breaking, it wasn’t just about moves or battles, it was about the lives, the stories, the emotion around the culture. That human side of things drew me in. Now I help lead the artistic direction of the magazine, and we try to make it a platform that goes beyond breaking, into the full spectrum of street culture and creative self-expression.

HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE BREAKERS MAGAZINE TO SOMEONE PICKING IT UP FOR THE FIRST TIME?

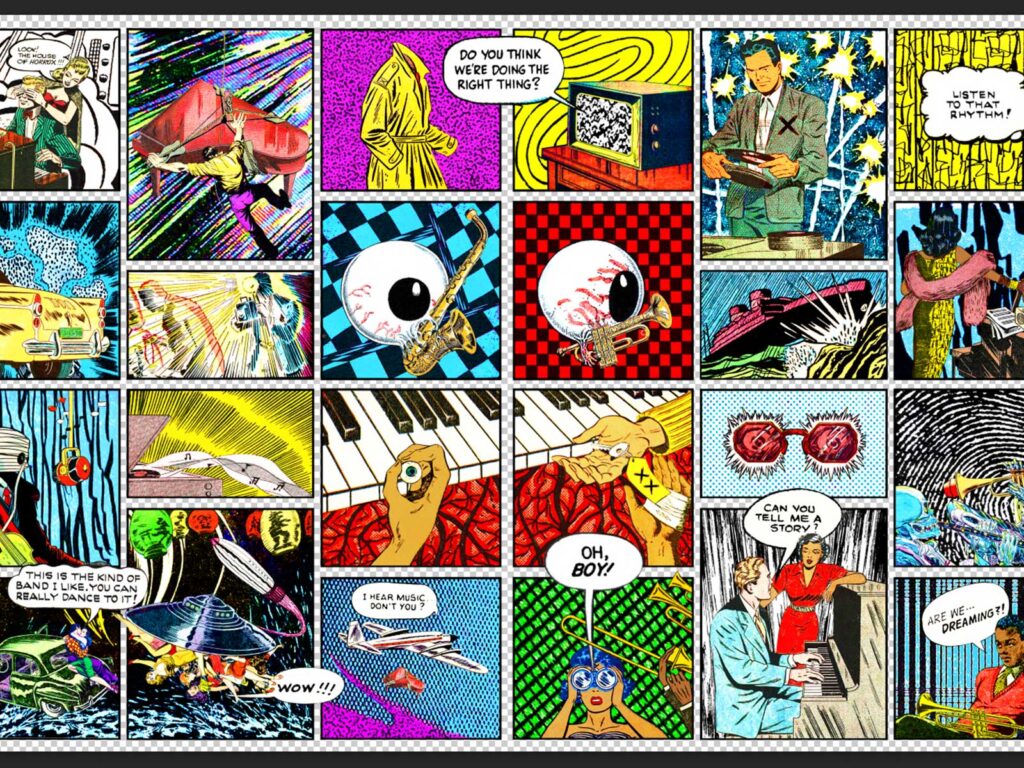

TOM: It’s a physical object first. That’s always been central to the vision, something tactile, something to hold. From the beginning, I didn’t want to build a website or chase SEO. I wanted to make something beautiful, like the surf and skate mags I admired. That kind of print culture never really existed in breaking, so we made our own. It’s bilingual, built from scratch, and it’s grown issue by issue alongside the people who’ve joined the project.

SEBASTIÁN: And it’s not just about breaking, it never really was. We use breaking as a way in, but what we’re really interested in is the people: their stories, struggles, creativity, and how culture lives in the everyday. For me, Breakers is a platform for all kinds of street culture, not just dancers, but skaters, DJs, photographers, writers, even academics. It’s a home for stories that aren’t always told, but that carry a lot of weight.

WHAT WAS THE ORIGINAL MOTIVATION BEHIND STARTING A PRINT MAGAZINE IN A DIGITAL-FIRST WORLD?

TOM: Honestly, digital never even crossed my mind. I wanted something physical, something you could leave out on a table, something collectible. That feeling of print as an object, not just a container for content. It wasn’t about starting a media company or building a brand. It was more instinctive: I love breaking, I love talking to people, and I wanted to make something that could archive all that in a way that felt meaningful. And to be honest, I also wanted to teach myself how to do everything, from editing to layout to building a website. The magazine gave me a reason to learn.

SEBASTIÁN: For me, it was about getting back to that feeling of permanence. As a designer, I’ve always loved books, posters, printed matter. I’ll buy something even if I don’t speak the language, just because of how it looks and feels. And I think print helps us slow down, it lets you sit with something, come back to it. It becomes an archive, a reference. Each issue of Breakers is a snapshot of the culture at that moment, and I think there’s value in that beyond the instant pace of online content.

WHAT’S THE HISTORY OF BREAKING IN FRANCE, AND WHY DO YOU THINK IT RESONATES SO DEEPLY HERE?

TOM: France has a long relationship with hip-hop, but breaking’s position here is still pretty unique. One reason is that, unlike rap or DJing, breaking was never tied to a product. You can’t sell a dance move. It’s not like skateboarding, where there’s a whole industry built around selling boards and shoes. In breaking, you’ve got music, a floor, maybe some shoes but that’s it. So the culture grew live, in the moment. You had to be there. And I think in France, that suited something about our creative spirit, especially in cities like Paris, where street culture has always had a strong presence. There’s a history here of reclaiming public space, performing in the street, and building scenes without needing permission.

HOW DO YOU DECIDE WHAT MAKES IT INTO AN ISSUE OF BREAKERS?

SEBASTIÁN: From the beginning, we’ve tried to keep a strong editorial structure, things like the photo portfolio, the “Talks” section, interviews with people inside and outside of dance. Some articles focus on breaking history, others are more abstract. We’ve even included fiction. What matters most is the voice and the perspective. We’re not interested in sport-style breakdowns or fitness routines. We want to know how people use breaking or hip-hop more broadly, to navigate their lives.

TOM: Exactly. We’re more drawn to the stories behind the moves. Breaking teaches you emotional intelligence, how to collaborate, how to fail and keep going. It’s a hustle. And once someone’s learned to move through all that, you know there’s a lot they can say about their environment, about culture, about themselves. We’re open to anything that carries that kind of depth, whether it’s a dancer or a photographer or someone writing about film. What links them is mindset. That’s what Breakers is really built around.

TOM: Tribe Tales came out of a feeling that we needed to bring people into the Breakers world, not just as readers, but physically into a space. The magazine is about building something slowly, with trust, with emotional intelligence. And the event was the same. We created a concept based on how crews work together: how they make decisions, how they choose who battles who. It’s not just about the best dancer, it’s about communication, about understanding your crew and how to support each other. The name “Tribe Tales” reflects that. We wanted to celebrate collectives and the way they move together.

SEBASTIÁN: And it wasn’t just the format, it was the energy. The second edition completely blew us away. So many more people than we expected showed up. It was full of love, of community. What made it special was that it didn’t stay inside one bubble, we had one day inside a library, with cyphers and DJ sets, and another with a party and a battle in a totally different venue. That contrast helped draw in new crowds. It’s what we always try to do: keep things rooted in breaking and hip-hop but also open the doors to anyone who wants to connect with the vibe. People came as crews, as friends, as families. That’s the kind of unity we care about.

BREAKING IS SOMETHING THAT TYPICALLY HAPPENS IN THE STREET, SO IS WILDPOSTING A NATURAL FIT FOR YOU? WHAT EXCITES YOU ABOUT THIS FORMAT, AND WHAT DO YOU HOPE THE POSTERS WILL ACHIEVE?

SEBASTIÁN: The wildposting campaign is a way for us to show that Breakers is much bigger than just breaking. The posters going up around Paris right now are designed to communicate the spirit of what we do, bridging hip-hop with other street cultures, and opening the door to new collaborators. We want people who don’t know the magazine yet to see something that makes them curious, that draws them in. And for those who do know us, it’s about reaffirming what we stand for: independence, creativity, and cultural connection.

TOM: One of the things you’ll see in the posters are quotes pulled straight from the pages of Breakers, lines that capture the energy, values, and voices of the people we feature. Things like “Ego is a dance.” We kept the design raw and direct: just the quote, the speaker’s name, and our logo. Because for us, wildposting isn’t just a marketing tool, it’s a continuation of our approach since day one. DIY, street-level, self-funded. Like breaking itself, it’s about being present in public space and sharing something real. This is how we reach people by being visible, not just online, but on the walls of the cities we care about.

HOW WOULD YOU COMPARE THE CREATIVE SCENES OF PARIS AND MONTPELLIER, YOUR TWO HOME CITIES?

TOM: Paris is amazing if you’re organised and know exactly what you’re aiming for, it’s full of opportunities, but also full of noise. So many creatives, so much competition. For me, Montpellier made more sense. I’ve got family here, and I’m not trying to do this full-time for a living. It’s still a passion. And here, you can build more stable relationships, more community. People trust you quicker. I linked with venues super easily, they believed in Breakers right away. In Paris, it might’ve taken longer to get that trust.

SEBASTIÁN: That’s it. In Paris, before people even give you a chance, you need the social network, the right references, all that. In smaller cities, like Montpellier, it’s more, “Okay, let’s talk, let’s do something together.” There’s less gatekeeping. And the crowds are more mixed. You’ll get families, young people, older people, people who’ve never seen breaking before all at the same event. It feels more open.

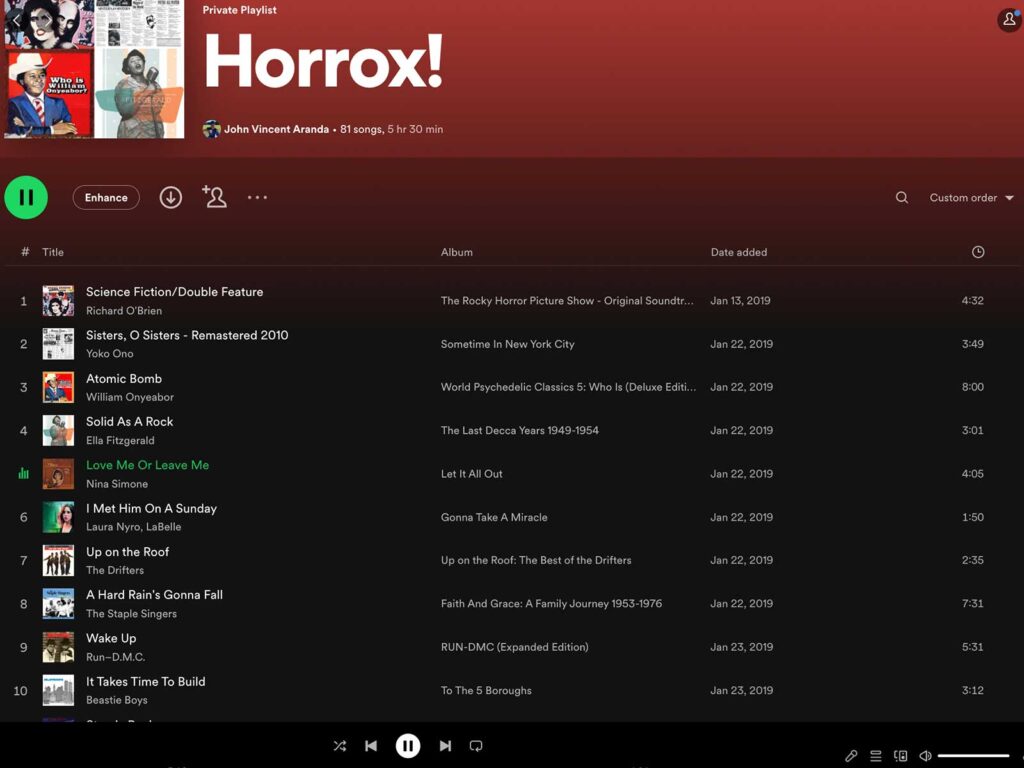

WHAT’S YOUR FAVOURITE PLACE TO HEAR MUSIC? IT DOESN’T HAVE TO BE IN PARIS…

TOM: Honestly? My car. These days, I spend so much time in it with my daughter that it’s where I listen to everything.

SEBASTIÁN: I’ve been enjoying smaller venues in Paris like New Morning, La Gare Jazz—places where you get live jazz jams with different line-ups every night. It’s raw and made for the moment. There’s also a good scene around Bastille with everything from rap to rock.

AND THE BEST PLACE TO DANCE?

TOM: My car, again… No, maybe a crowded room with tight cyphers, or a techno afterparty. Anywhere with energy bouncing off the walls.

SEBASTIÁN: I don’t break, but I love to dance, especially to Latin music. I’ll go wherever there’s movement, even if it’s a reggaeton night. But honestly, any place with a good vibe and a fast two-step works for me.

HOW CAN PEOPLE SUPPORT BREAKERS MAGAZINE?

TOM: The best way is just to reach out. Write to us, share your ideas, show us your work. We’re always open to building something interesting together, whether it’s editorial, design, photography, or events. It doesn’t have to be big or polished. We’re a collective at heart, and collaboration is what’s kept this whole thing alive.

SEBASTIÁN: Yeah, and it’s not really about money. Of course, funding would give us more time to dedicate to the project, but what we’re really looking for is connection. People who get what we’re doing and want to contribute creatively. Writers, designers, editors, cultural workers. If you see a way to build with us, let’s talk.