“This mattered. This deserves to be remembered.”

That’s part of the ethos of Queens-raised, Brooklyn-based artist Emily Manwaring. Her paintings and sculptures capture moments, memories, and joy – like a shared camera roll for New York’s Caribbean community. From busy dancefloors to self-care in solitude, from Haitian Tap Tap buses to the changing streets of the Brooklyn, Manwaring collects hundreds of references for each piece she lovingly curates: smartphone photos, items found on the streets of her Flatbush neighbourhood, flyers for dancehall raves from yesteryear, and jewellery lost and found at Carnival.

Her work – both finished and in progress – is the backdrop of our interview as she chats from her apartment during New York’s bleak mid-winter. The art warms the scene, combining brushstrokes, dyed canvases, and real-life artefacts to create something transformative: future artefacts, archives of culture that, in her own words, “hasn’t been preserved or remembered in the ways it deserves to be.”

This approach is evident in works like ‘SoUNd Bath’, where two women bask in sunlight and sound, a pink iPod Nano by their side as they share headphones. It’s a scene as intimate as it is universal – a snapshot of quiet joy shared between friends. For Manwaring, these moments of closeness, especially among women, are at the heart of her art. Her early fascination with family photo albums – frozen frames of love and connection – inspired her to honour these relationships on a larger scale.

Inspiration has also come from artists like Kerry James Marshall and Jordan Casteel, both of whom showed her how identity could take up space on a gallery wall. But Manwaring’s early experiences in Queens were equally formative. With limited access to the arts in her hometown, she would often cut school to visit galleries in Brooklyn or Manhattan. Those trips, along with her time working at the Studio Museum in Harlem, taught her to value art as a form of storytelling and preservation.

Manwaring’s work has been featured in prominent galleries such as Thierry Goldberg, Great Hall Gallery, Swivel Gallery, and Monti 8 in Italy. She’s also received critical acclaim in publications like The New Yorker, JUXTAPOZ, Artnet, and It’s Nice That. Most recently, she was selected to exhibit in the Brooklyn Museum’s Brooklyn Artists Exhibition – a significant milestone that cements her place among the city’s most exciting emerging artists.

Yet her work is not confined to galleries or institutions – if anything, the idea of having it on the streets excites her more. Her art thrives in public spaces, where it can directly connect with the communities it reflects.

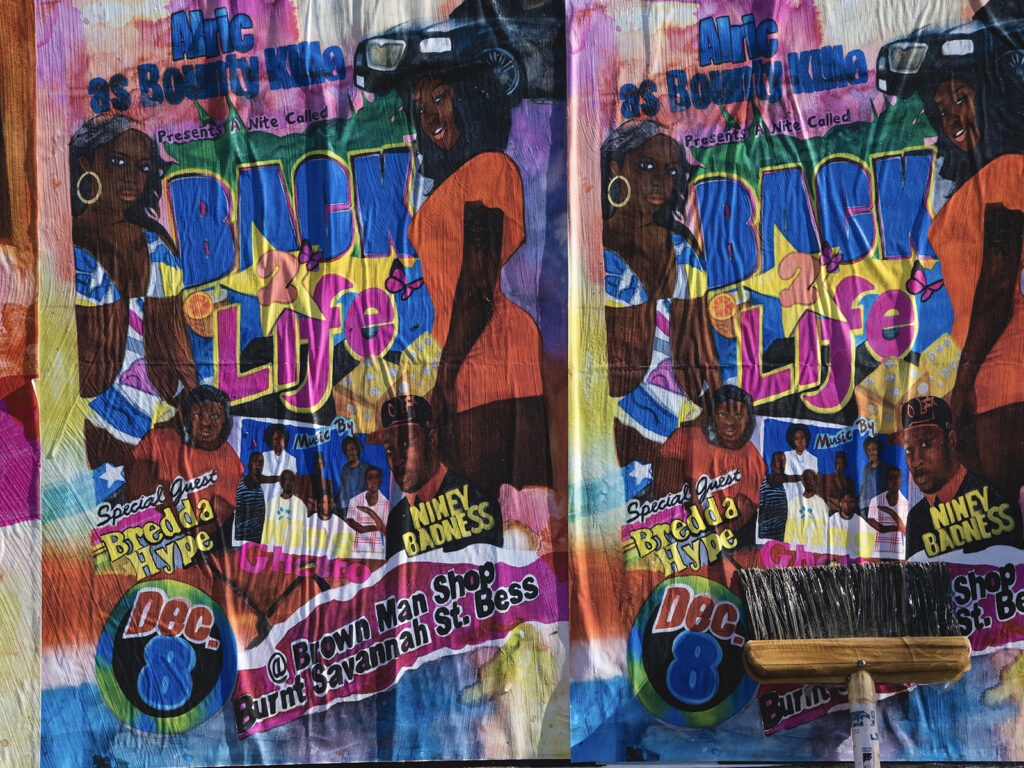

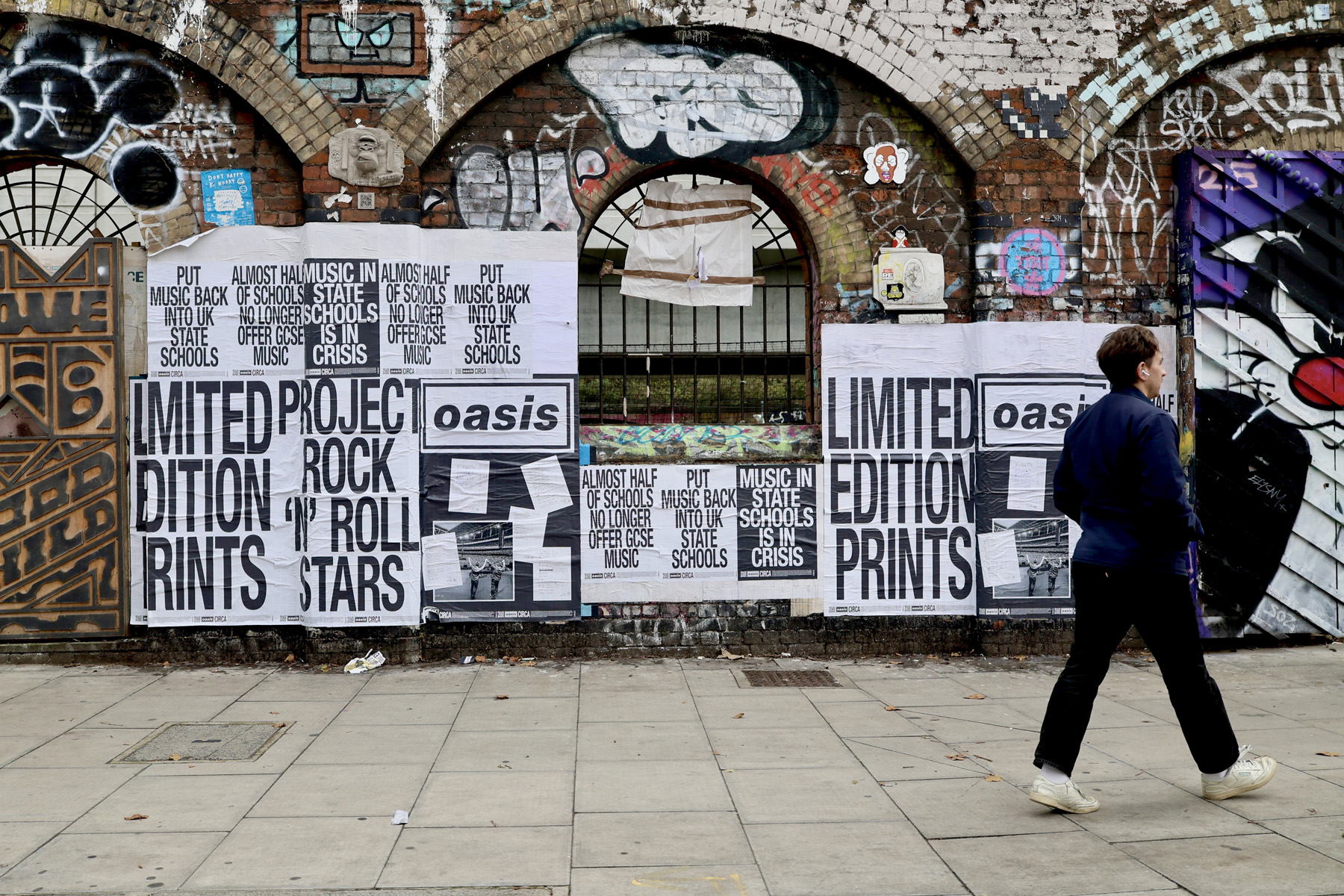

Her collaboration with UNCLE brings her Back 2 Life project to these public spaces. Inspired by dancehall flyers’ bold colours and compositions, this work reimagines those designs at a monumental scale. “I’m imagining an auntie walking past one of my wild posters and seeing herself in it,” Manwaring says.

Archiving moments and shared memories, her art takes up space where it matters most – on the streets, where stories of joy can be celebrated by the people they belong to.

HOW DO YOU APPROACH A NEW PROJECT OR IDEA? COULD YOU WALK US THROUGH YOUR CREATIVE PROCESS, FROM INITIAL INSPIRATION TO THE FINAL PIECE?

It often starts with a memory – a specific moment that sticks with me—and I begin thinking about how I want to bring that to life. From there, I map out the composition, especially if I’m working with a square canvas. I’ll think about what’s happening in each corner, what’s coming out of the frame, and how the shapes will work together. Sometimes I break the frame entirely and explore how to present the work in a completely different way.

I use a folder filled with references – hundreds of photos for a single painting. It might be a colour I noticed on the street, the texture of a feather on the pavement, or the way jewellery sparkles. I also take my own reference images, which might capture a pose, an outfit, or the way light hits a certain surface. All of these pieces come together to create something cohesive – a sort of amalgamation of all these little inspirations.

I also think a lot about 3D elements. What can pop out of the canvas? How can I ground the viewer in the world I’m creating?

TELL US ABOUT THE ROLE OF MATERIAL AND THESE 3D ELEMENTS IN YOUR WORK… HOW DO YOU CHOOSE THEM?

My boyfriend and I are always collecting things we find on the street – flyers, objects, anything that feels like it could spark inspiration. Those materials sometimes end up in my work, and I love the idea that they bring a piece of the world into what I’m creating.

Materiality is so important to me because it bridges the world I’m creating in my art with the real, tangible world around us. When I include objects like a bracelet, a necklace, or even concrete, they act as grounding techniques. These elements bring familiarity – they make people stop and think, “I know that; I’ve worn that; I’ve seen that before.” It draws them into the piece, helping them feel connected to the world I’m portraying.

For example, I did a painting with a hammock, and I used lamps to hold it up. Those lamps weren’t just decorative; they became part of the sculpture, part of the functionality and presentation of the work. It was about making the piece feel alive, like it existed in a space rather than just on a canvas.

WE’VE ALREADY SPOKEN ABOUT JOY AND CARIBBEAN CULTURE, BUT ARE THERE ANY OTHER THEMES THAT ARE CENTRAL TO YOUR WORK?

A lot of my work is centered around women and the interactions we have with each other. It’s about what it means for me to be a woman and the spaces where we find connection, joy, and sanctuary. Those moments of interaction, whether they’re big or small, are something I love to explore through my paintings.

“Back 2 Life” is inspired by flyers for dancehall waves, combining nightlife and visual culture in such a striking way. Could you tell us about the inspiration behind this piece and how it fits into your broader body of work?

Back 2 Life is such a special piece for me because it represents a shift in my practice. It was one of the first times I broke free from the square frame and traditional stretcher bars to really ask myself: What am I trying to say here? The inspiration came from walking around Brooklyn, especially in Flatbush, and seeing all these incredible Jamaican and Caribbean flyers pasted up everywhere.

There’s something about the composition of those flyers – the colours, the faces, the text—that feels so alive and futuristic, even though many of them come from years ago. I started collecting them, building this archive of visuals, and one flyer in particular stood out to me. It became the foundation for Back 2 Life.

The process was just as important as the inspiration. I began by dyeing the canvas, letting the colours bleed and interact with each other naturally. That was like creating a living, breathing base layer. Then I started layering the imagery on top – rendering the figures, adding the vibrant text elements, and blowing up the flyer’s scale to almost command the space it’s in.

What’s exciting about this piece is how interactive it feels. People look at it and ask themselves, “Is this a real event? Should I call the number on the flyer?” It creates a sense of curiosity, almost like the flyer is coming alive again. For me, this work is a way to honour the visual culture of the Caribbean diaspora and to get it back on the streets.

DO YOU SEE PAINTING AS A USEFUL WAY TO ARCHIVE?

I definitely see painting as a form of archiving, especially for Caribbean culture. There’s so much that hasn’t been preserved or remembered in the ways it deserves to be. When I was younger, I’d spend hours looking through my family photo albums and thinking about how to honour those moments in a new way. That’s how I first started painting, by recreating those photos and reflecting on what they meant to me.

Now, my work has grown to include not just personal memories but collective ones too. I’m working on a piece right now that holds objects you’d find during Carnival, like pieces of jewellery or feathers and that’s another way of capturing these moments that are so rich but often fleeting.

For me, painting is about saying, “This mattered. This deserves to be remembered.” It allows me to take fleeting or ordinary moments and transform them into something lasting, something people can look at and connect with for years to come.

WHAT’S BROOKLYN LIKE AS A PLACE TO LIVE AND WORK AS A CREATIVE?

Living in Brooklyn is just amazing. I don’t want to talk too deeply about Flatbush because I don’t want them coming in and gentrifying all my shit. But being here is so special to me, it’s full of Caribbean culture, and it feels like home in every way.

I take what I call grounding walks, where I’ll just go out and photograph anything that inspires me the colours, textures, moments. Brooklyn has so much life and history; you’ll see something on the street that unlocks a memory from years ago, and suddenly, I’ll want to create a whole body of work based on that.

I walk down the street and I’m a reflection of it.

WHO ARE SOME OTHER ARTISTS FROM NEW YORK WE SHOULD KNOW ABOUT?

I have to shout out my boyfriend, Oji Haynes, he’s an all-around artist who works in photography and sculpture. Our home is filled with our creations, and it’s such a unique way to live and collaborate.

I’ve gotta shout out my friends, basically. Tyinghe Fleming who works in photography and Aicha Cherif who works in cinematography, directing and production. What I love about New York is this culture of mutual support, we’re all pushing each other to create and grow.

FAVOURITE PLACE TO SEE ART IN NYC?

MoMA holds a special place in my heart. It was the first major museum I explored as a teenager, often skipping school just to spend hours there. Those early visits shaped my understanding of what art could be.

I also love the galleries in Chelsea, where you can find some of the most inspiring contemporary shows. And of course, the Brooklyn Museum, it’s such a dynamic space that feels connected to the community.

FAVOURITE MUSIC VENUE IN NYC?

Brooklyn Paramount is a standout for me I’ve seen some incredible shows there, like Chief Keef and Cash Cobain. It’s got that real New York energy.

Another favourite is Nowadays, where I’ve danced until the early hours with friends. Those DJ sets mean so much to me, music and dancing are such important parts of my life. Dancing is definitely my love language. If I weren’t a painter, I think I’d be a dancer!

FAVOURITE PLACE TO GET FOOD IN NYC?

I’d have to say Brooklyn. I love Fisherman’s Cove – unfortunately they’re taking it down due to gentrification, but that’s the best ox tail.

Your art belongs in the physical realm, but much of its audience discovers it online. What challenges do you face translating the vibrancy of your work to digital spaces, and how do you approach sharing it on platforms like Instagram?

Instagram is weird, but it’s also necessary. For me, it’s like a LinkedIn now, just a way to connect with people and share what I’m doing. I grew up in the Tumblr era, and I think I still treat Instagram like a blog, posting things that remind me of different moments in my life or my work.

I try to use it as a tool to show my process or highlight parts of my paintings, but it will never compete with seeing the work in person. When someone sees my art online, I hope they feel drawn to come experience it physically because it’s a completely different energy. Social media is useful, but I value real human interactions and the experience of seeing art in real life so much more.

WITH YOUR UPCOMING COLLABORATION INVOLVING WILDPOSTING IN NEW YORK, WHAT EXCITES YOU MOST ABOUT DISPLAYING YOUR ART IN PUBLIC SPACES?

What excites me most is how accessible it is. Art shouldn’t only exist in galleries or fairs, it should be part of the world, on the streets, in places where people actually live their lives. With this project, I’m imagining someone in Flatbush walking past a billboard or a wild poster and seeing themselves in it, seeing their culture reflected back at them.

There’s one scenario that keeps coming to mind – aunties, the elders in our community, walking by and seeing themselves or their stories represented. Maybe it’s someone who hasn’t had the chance to go to a gallery or a museum, but they look at that poster and feel seen. That’s what I love about this format, it’s for everyone.

It’s not locked behind closed doors or dependent on who can afford to visit a gallery. It’s right there for people to engage with, and that feels really powerful. The streets are full of stories, and this is my way of adding to that, of giving something back to the community while connecting with people in a real, direct way.